International education remains one of the most dynamic, high-impact global systems of the modern era; a powerful force that delivers shared prosperity for learners, destination markets, home countries, and employers alike. The QS Global Student Flows report offers an evidence-based framework outlining three scenarios for international education through 2030—Regulated Regionalism, Hybrid Multiversity, and Talent Race Rebound. Each scenario considers geopolitical developments, technological advancements, demographic shifts, and economic transformations, equipping decision-makers with the tools needed to anticipate and adapt to the future.

Executive summary

Low growth shifts the battleground to differentiation

Through to 2030, international student recruitment in both Australia and New Zealand (NZ) is expected to stagnate following a post-COVID boom period in Australia and a slower recovery in NZ, with forecast growth of 2% and 5% respectively. China and India are projected to remain the primary sources for international students for both countries. Geopolitical factors restricting demand, combined with the rising reputation and openness of new destinations are critical drivers behind this stagnation.

As global demand for Australia and NZ’s higher education plateaus, competition from nations outside the “big four” is intensifying - our Global Student Flows data forecasts that Asia and the Middle East will grow as destinations as they compete to become regional hubs.

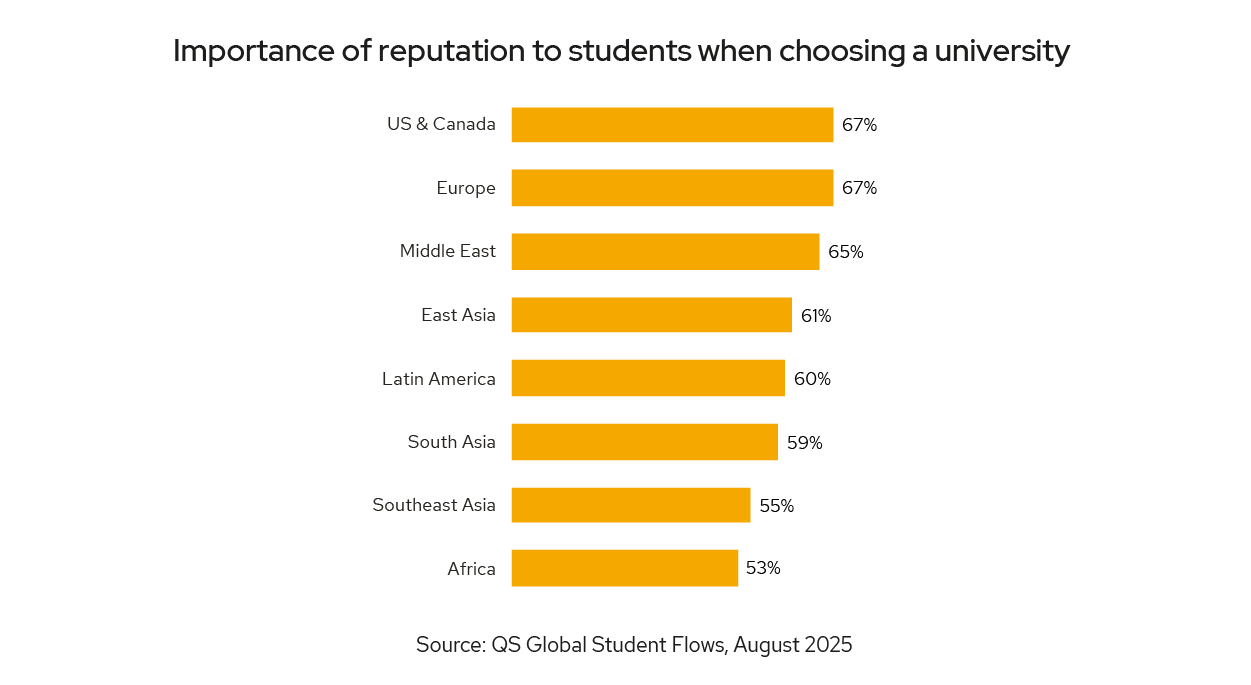

Students are becoming more selective, and driven by institutional reputation, inclusiveness, and post-study outcomes. In a low-growth environment, where growing market share is the key to success, institutions need to prove their value proposition and demonstrate clear return on students’ investment. However, while data from the QS Academic and Employer Reputation Surveys show that the top universities in Australia and NZ are maintaining their Academic Reputation year on year, the ‘average’ university has a declining reputation among these key stakeholder groups. Simultaneously, institutions in emerging study destinations across Asia are enhancing their performance on this key metric. To win, universities will need to leverage and communicate their unique reputation and outcome-based strengths as competition intensifies domestically, as well as globally.

Labour market alignment and employment outcomes will be key to outperform the market

Both Australia and NZ face persistent shortages in high-skilled labour, particularly in healthcare, engineering, technology, and education. These structural gaps in the domestic workforce create a strong demand-side pull for international talent. When aligned with clear, stable migration pathways, international education becomes a reliable talent pipeline - allowing economies to upskill and increase productivity. In this context, international students become a key lever in long-run human capital strategy, rather than temporary residents.

For Australian universities, this is a challenging area as the federal government responds to domestic pressure to slow migration, while, in contrast, the NZ government has recently moved to change student visa-related policies and settings to attract international students to the country. However, according to data from the QS World Future Skills Index, both countries are challenged when it comes to the satisfaction of employers with the skills of their graduates today. This is further emphasised by QS World University Rankings data - over time Australian universities have dropped on average by 238 places for Employer Reputation and NZ universities have dropped universities by 191 places. Addressing this mismatch will be vital to future success.

Data from the QS International Student Survey highlights that students are increasingly looking for reassurance that their course will put them on the right career path through work placements and upskilling opportunities during their studies. Aligning programme portfolios to labour market needs and adopting more agile curriculum development practices will help in ensuring key skills are being taught.

Diverging political strategies may bring about different fortunes

Despite facing similar headwinds, the two nations are currently adopting very different approaches to international education. Responding to a general anti-migration sentiment, fuelled by an accommodation crisis, Australia’s policy environment has become increasingly stringent over the past 18 months with price increases that have seen the student visa fee become the most expensive in the world. Such shifts are threatening to further depress the forecast 2% growth in coming years. NZ, on the other hand, has yet to reach its pre-COVID number of international students, and the government has recently announced a goal of doubling revenue from the sector by 2034, with changes to student visa settings already implemented and a shift from diversification of the student cohort to a focus on three key markets.

Aside from policy changes, Australia’s higher education fortunes have the potential to change. In the QS World Future Skills Index, Australia’s Academic Readiness is among the best in the world meaning Australian higher education is ready to adapt and deliver the future oriented skills required by employers. Australia has a strong foundational perception in-market, being known among prospective students for good quality of life, work opportunities and safety, and is not especially known for its challenging visa process (QS Country Perceptions Survey 2024), but this perception is at risk due to the less than welcoming policy environment.

NZ is well positioned to actualise its ambition for growth. A welcoming environment is the top priority for students looking to study in NZ when deciding on a country, and its recent strategy announcement to welcome 35,000 additional international students by 2034 will only help its perception. The country is building a strong future talent foundation, shaped by high-quality education, a values-driven workforce, and growing capability in sustainability-aligned sectors.

Three scenarios to help navigate future uncertainty

The Global Student Flows Initiative 2025 uses three scenarios grounded in extensive research as a lens through which to understand the medium-term outlook of higher education in the region within the global context: Regulated Regionalism sees Australia and New Zealand remaining as key study destinations, but enrolment becomes selective, transparent, and aligned to national goals. Hybrid Multiversity would see students complete most of their education online or at domestic institutions before travelling to Australia or New Zealand for shorter, focused in-person experiences. In a Talent Race Rebound scenario, national and regional governments would reposition international education as a pathway to attract talent and fill skills gaps. Institutions need to effectively scenario plan to mitigate the risks and opportunities associated with these scenarios, enabling them to stress test their strategic thinking and navigate uncertainty.

TNE provides a potential solution

For both countries, transnational education (TNE) could offer an alternative pathway towards financial stability. Though static international student numbers and constrained budgets may make offshore TNE unfeasible for many institutions, migration policy continues to be the focus of public debate, especially in relation to the housing crisis, meaning there is increased interest from Australian universities in the TNE space. Southeast Asia also continues to be a focus for TNE, including online provision. As concerns grow regarding the accessibility and affordability of an onshore Australian education for many in the region, TNE offers a significant opportunity as students look to study closer to home and reduce the cost of study and living. No NZ university has announced plans to operate a campus offshore, but Education NZ’s recently launched strategy does reference TNE as a contributor to the revenue goals set for the international education sector to achieve by 2034.

Strategic challenges

1. Market position and differentiation

How can universities in Australia and New Zealand develop distinctive value propositions that resonate with increasingly selective international students, particularly in a low-growth market dominated by China and India?

2. Reputation and competitiveness

What targeted strategies can universities outside of the upper echelon adopt to reverse declining Academic and Employer Reputation scores, and close the gap with both top-ranked domestic institutions and rising competitors in Asia?

3. Labour market alignment

With skills gaps apparent, how can higher education institutions better align programme portfolios, curriculum design, and work-integrated learning opportunities?

4. Policy and migration pathways

What coordinated actions can universities, government and industry take to create policy environments that both address domestic concerns - such as housing and migration - and foster new long-term growth of the international education sector?

5. Transnational education as a growth lever

What models of transnational education - branch campuses, online delivery, or hybrid formats - can be most effectively deployed to capture demand from students in Asia and the Middle East who seek more affordable, accessible alternatives to onshore study?

2030 outlook

Stagnant growth and intensifying competition

Total enrolments in Australia’s international student sector are projected to reach 770,000 by 2030 in our baseline scenario. This is equivalent to 2% annual growth (the total student number includes students in higher education, English language, and non-award courses, but excludes those in vocational training). While this growth rate marks a slowdown from the long-term average of 8% and the post-COVID rebound of 5%, it reflects a broader cooling across major study destinations.

The sector has reached an inflection point - no longer is it defined by rapid expansion, but by how it manages risk, diversification, and policy recalibration. Dependencies built over the past two decades on China and India are now raising tough strategic questions. In Australia the expansion started in the early 2000s when China’s share of international students in the country more than doubled - from 9% in 2000 to over 20% within five years. India and its South Asian neighbours also overtook many East and Southeast Asian markets, both in numbers and share of enrolments during this period. But that momentum has brought new challenges, especially as reliance on a narrow group of markets highlights the vulnerabilities in Australia’s fourth-largest export industry.

In the period to 2030, China and India are projected to remain the primary sources of growth in student numbers. Rising geopolitical friction with the US may further increase Australia’s appeal for Chinese students, while India’s expanding youth population and economic trajectory signal ongoing growth. Among Australia’s other top source markets, there are signs of renewed activity. Countries like Indonesia, Taiwan, South Korea, and Singapore, which have historically seen flat or declining student numbers over the long term, posted a notable increase in visa approvals in the second half of 2024. But with ageing populations and signs of saturation, sustained growth from these markets over the longer term is less likely.

Policy shifts, such as higher visa fees introduced in 2024, have already impacted English language enrolments, especially from Latin America, where most students are concentrated in this segment. Still, demand from the region had been rising steadily until that point, and there’s potential for recovery if pricing and visa settings are recalibrated.

Structural headwinds in main source markets - such as China’s own economic slowdown and efforts to bolster domestic universities - pose downside risks to the outlook. Domestic politics and geopolitics also remain a wildcard, as the experience during COVID highlighted how broader political dynamics can shape education ties. India’s outlook is more demand-driven, underpinned by favourable demographics and economic growth. But growth from this region is likely to be capped by Australia’s more restrictive visa policies. Alongside practical hurdles, this creates perception risk - adding an element of uncertainty for prospective students.

In contrast to Australia, NZ, accounting for around 5% of the combined international student market across the two countries, has more room to grow, with projected annual growth of 5%. The country is still recovering from a slow post-COVID rebound and remains at just 83% of 2019 levels. However, a more welcoming policy environment, particularly for students from South Asia and Africa, is set to position NZ favourably as Australia adopts a more restrictive stance.

.jpg)

With projected growth of 2% per year, Australia ranks second among the top four study destinations, behind the UK. Growing concerns around safety and policy uncertainty in North America are likely to divert students toward more predictable markets. Yet, Australia’s own policy tightening risks creating a perception barrier that could limit its advantage. There is also increasing competition from within Asia Pacific. At the start of the millennium, Singapore, Indonesia and Malaysia ranked among Australia’s top source countries. Today, all three are positioning themselves as regional education hubs, shifting from partners to competitors in the battle for Asia Pacific’s students. But Australia maintains a strong TNE footprint in East Asia, with numerous branch campuses in Malaysia and Singapore. This presence positions it well to capture growth as more students study within the region. Nearly half of its offshore campuses are in Southeast Asia, particularly in Malaysia and Singapore.

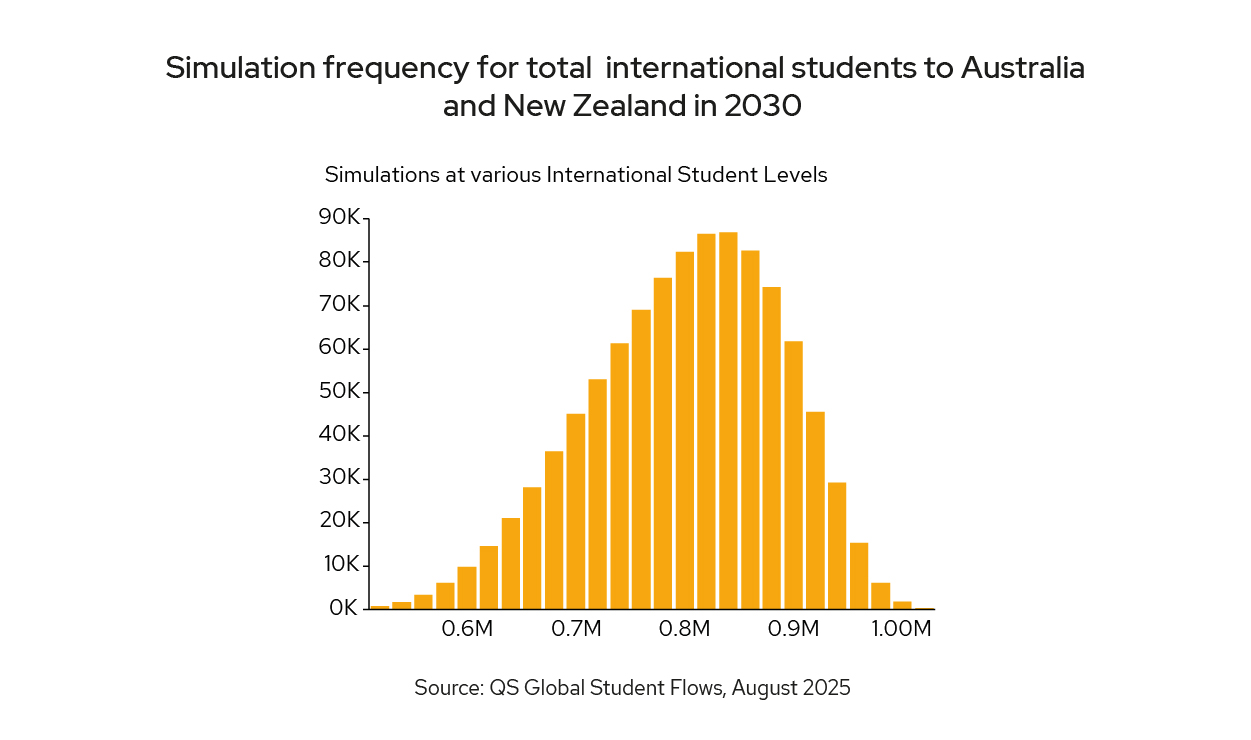

While our base case remains cautiously optimistic, downside risks should not be ignored. A sharper slowdown in China, financial instability in key markets, or further tightening of migration settings could undercut growth. Conversely, an upside scenario - driven by continued redirection from North America, stronger recovery in Southeast Asia, and stable geopolitics - could see stronger gains for both Australia and NZ.

Our methodology

Global Student Flows initiative

The Global Student Flows (GSF) initiative comprises three core components: QS’ Open Source Framework for Global Student Flows, a proprietary Flow Mapping and Analytics Technology, and a Scenario-Based Forecasting Methodology designed to simulate over 4,000 discrete source-to-destination flows. Together, these instruments offer a comprehensive, 360-degree view of the global outlook for international student mobility.

QS International Student Survey

The QS International Student Survey offers an unparalleled view into pre-enrolled international students. The 2025 iteration draws on responses from over 70,000 students in 191 locations. The questions in the Survey are designed to enable higher education institutions to make sound decisions on recruitment and communication strategies. Now combined with Global Student Flows data, we offer a well-rounded view of where students are choosing to study, and how they make that decision.

Access more information about the methodology in the full report.

International student trends

Student decision-making increasingly driven by reputation

Reputation as a driver of student decision making is at a fascinating crossroads. While students increasingly look to reputation and career outcomes to make decisions, the reputation of institutions in NZ and Australia is declining or plateauing. The average Academic Reputation rank of all Australian institutions has declined from 436 in 2017 to 522 in the QS World University Rankings 2026.

At the same time, there is a cohort of nations who have seen their reputation rapidly grow, but lack the capacity, infrastructure and career outcomes to become significant destinations. The United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait have all seen their top universities raise their Academic Reputation by 179, 124 and 201 places respectively. Brazil has also improved its average Academic Reputation by 90 places, with India rising by 29 places on average.

The value prospective students place on an institution’s reputation differs depending on where they are from. However, regardless of home country, reputation remains important for over 50% of students, further emphasising the challenges Australia and NZ institutions face with their declining and plateauing reputation.

When looking at all prospective students, that their studies lead to their chosen career has been one of the top three priorities when making decisions about which course to study for over five years. This should cause alarm among institutions in NZ and Australia, given the declining Employer Reputation seen since 2017. Without being able to show strong career outcomes, NZ’s good work in building a positive perception may not be as impactful.

The reputation of institutions among employers is something which can be significantly influenced by the outcomes of its graduates.

In New Zealand, institutions are able to deliver positive graduate outcomes, securing high graduate employment rates and producing graduates who have gone on to make a meaningful impact on society. Leveraging such successful narratives will be critical to reversing the decline in New Zealand’s reputation among employers, which is currently significantly lower than its graduate outcomes would suggest.

In Australia, there is a markedly different story where Employment Outcomes for institutions are marginally worse than their reputation among employers. This reiterates the point that Australian institutions need to make graduate employability a core component of existing and upcoming curricula development. Ensuring that graduates have the appropriate mix of skills to meet the existing and future demands of local employers should be central to this strategy. In doing so, institutions can transform their capacity to become drivers of economic growth and enhance their reputation among employers.

Employability is a vital consideration for prospective students

Post-study employment prospects are a vital consideration for most students - just under half prioritise their career path when choosing which course to study. Information on work placements and links to industry is the most desired marketing communication strand for candidates looking to study in Australia. It’s especially important to communicate this information to East and South Asia candidates who place higher importance on this than students in other regions. With over 150,000 students from South Asia projected to study in Australia and New Zealand by 2030, it’s crucial for institutions to focus on this area if they are to grow. The ability to learn new skills is the most important career consideration for candidates. They see their time at university as the best time in which to upskill and to learn how to articulate the value they can add to prospective employers with the skills they acquire there.

Student origins

In our baseline scenario, Australia’s international student numbers are set to grow at a modest pace of around 2% annually through 2030. That would take the total from around 680,000 students today to just under 770,000 by the end of the decade (the total figure includes students enrolled in higher education and English language courses but excludes those in vocational training). It marks a notable slowdown from the pre-COVID boom, when student numbers grew at nearly 10% per year over the six years up to 2019.

The deceleration isn’t unique to Australia. A combination of slower economic growth in major sending countries - particularly China - and tighter policy settings in host countries is dampening momentum across the global education sector. In this context, Australia is expected to see the second-fastest growth among the major Anglophone destinations, behind the UK.

Unsurprisingly, China and India will remain the twin engines of growth. Combined, they already make up 43% of Australia’s international student intake, and that share is set to rise to 46% by 2030. But the paths for each are diverging. China’s numbers will be shaped by broader economic headwinds at home and the ongoing geopolitical recalibration. These very tensions - especially with the US - are likely to make destinations like Australia and the UK more attractive as a study destination. India, meanwhile, is experiencing strong demand, but Australian visa policies may become a constraint. The recently tightened Genuine Student Test (GST), for example, could act as a brake on growth from India and other South Asian markets. The ramifications of such policy changes could be significant as they would affect a unique component of Australian higher education. Australian universities are significantly more diversified in where they enrol their international students from. In 2024, only 38% of their international students came from China or India, compared to 43% going to the UK and 54% to the US. Australian institutions recruit a far greater proportion of international students from secondary markets in Latin America, South and Southeast Asia. A likely impact of the Genuine Student Test would be to restrict those numbers coming from secondary markets meaning institutions would become more reliant on China and India for their students.

Beyond the top source markets, several Asian markets are gaining ground. Vietnam and Indonesia are expected to climb the ranks of the top source markets, while others like Brazil, Colombia, Thailand, and South Korea are seeing a slide, and have struggled to recover since the pandemic. This decline may reverse should the additional engagement with Southeast Asia be successful following Australia’s 2026 National Planning Level increase of 25,000 places. Countries such as Brazil, Colombia, and Spain - where over 80% of students in Australia are enrolled in English courses - have also seen persistent drops in enrolment since 2024, with little sign of reversal. Japan, where English language students account for about 70% of outbound students to Australia, is on a similar trajectory.NZ, though smaller in scale, is on a faster track compared to Australia, partly on account of its slower recovery from the pandemic so far. Apart from Africa and North America, all other regions have recovered to only 70% of 2019 levels so far, but the recovery is expected to pick up more quickly in the next few years. International student numbers in universities and English language schools are forecast to grow by around 5% annually through 2030, lifting enrolments from 38,000 in 2024 to roughly 50,000. Even so, this would bring numbers to just over 80% of the 2019 total. The projected growth rate is also lower than the 7% achieved between 2015 and 2019 and the New Zealand government’s 8% growth target in overall international student numbers for 2024–2027.

In our baseline scenario, Australia’s international student numbers are set to grow at a modest pace of around 2% annually through 2030. That would take the total from around 680,000 students today to just under 770,000 by the end of the decade (the total figure includes students enrolled in higher education and English language courses but excludes those in vocational training). It marks a notable slowdown from the pre-COVID boom, when student numbers grew at nearly 10% per year over the six years up to 2019.The deceleration isn’t unique to Australia. A combination of slower economic growth in major sending countries - particularly China - and tighter policy settings in host countries is dampening momentum across the global education sector. In this context, Australia is expected to see the second-fastest growth among the major Anglophone destinations, behind the UK.

Unsurprisingly, China and India will remain the twin engines of growth. Combined, they already make up 43% of Australia’s international student intake, and that share is set to rise to 46% by 2030. But the paths for each are diverging. China’s numbers will be shaped by broader economic headwinds at home and the ongoing geopolitical recalibration. These very tensions - especially with the US - are likely to make destinations like Australia and the UK more attractive as a study destination. India, meanwhile, is experiencing strong demand, but Australian visa policies may become a constraint. The recently tightened Genuine Student Test (GST), for example, could act as a brake on growth from India and other South Asian markets.

The ramifications of such policy changes could be significant as they would affect a unique component of Australian higher education. Australian universities are significantly more diversified in where they enrol their international students from. In 2024, only 38% of their international students came from China or India, compared to 43% going to the UK and 54% to the US. Australian institutions recruit a far greater proportion of international students from secondary markets in Latin America, South and Southeast Asia. A likely impact of the Genuine Student Test would be to restrict those numbers coming from secondary markets meaning institutions would become more reliant on China and India for their students.

Beyond the top source markets, several Asian markets are gaining ground. Vietnam and Indonesia are expected to climb the ranks of the top source markets, while others like Brazil, Colombia, Thailand, and South Korea are seeing a slide, and have struggled to recover since the pandemic. This decline may reverse should the additional engagement with Southeast Asia be successful following Australia’s 2026 National Planning Level increase of 25,000 places. Countries such as Brazil, Colombia, and Spain - where over 80% of students in Australia are enrolled in English courses - have also seen persistent drops in enrolment since 2024, with little sign of reversal. Japan, where English language students account for about 70% of outbound students to Australia, is on a similar trajectory.

NZ, though smaller in scale, is on a faster track compared to Australia, partly on account of its slower recovery from the pandemic so far. Apart from Africa and North America, all other regions have recovered to only 70% of 2019 levels so far, but the recovery is expected to pick up more quickly in the next few years. International student numbers in universities and English language schools are forecast to grow by around 5% annually through 2030, lifting enrolments from 38,000 in 2024 to roughly 50,000. Even so, this would bring numbers to just over 80% of the 2019 total. The projected growth rate is also lower than the 7% achieved between 2015 and 2019 and the New Zealand government’s 8% growth target in overall international student numbers for 2024–2027.

With a more open approach to students from South Asia and Africa, NZ could see an upswing in demand, particularly from countries like Sri Lanka, Vietnam, Brazil, and Colombia. That openness also positions it as an attractive alternative for students discouraged by tighter policies in Australia.

Demand for ANZ’s English language sector remains soft. English language courses now make up just 30% of international students, down from 50% in 2000. Post-pandemic recovery has been slow - the Australian government increasing visa fees will not help with this price-sensitive market. The improving provisions of English language teaching globally may suppress demand further.

In 2000, when Australia hosted just over 100,000 international students, China accounted for 9% of the market. Now, it’s around 30%. India has climbed from eighth to second place, with its share rising from 4% to 14%. In 2000, all but one of the leading markets were in East or Southeast Asia. Today, South Asian and Latin American countries have started to displace long-time regional partners like Malaysia (down nine spots), Singapore (-17), South Korea (-12), and Japan (-8).

Several of these countries, such as Indonesia and Malaysia, are attempting to build their own international education hubs. But with stronger economic fundamentals and growing middle classes, they still represent valuable source markets. Indonesia, once Australia’s top sender, has shifted focus towards the UK. For Australia, re-engaging with these mid-tier markets could be key - especially as visa scrutiny places a cap on growth from South Asia

The three scenarios for higher education in 2030

Regulated Regionalism

Regulated Regionalism describes a scenario in which international education becomes more regionally distributed and governed by formal national frameworks. In this model, major anglophone destinations - such as Canada, Australia, and the UK - implement structured policies to manage international student enrolments through transparent, annually reviewed thresholds and controls. These thresholds are calibrated against factors such as housing availability, institutional support capacity, and national or regional labour market priorities. Institutions are required to demonstrate their ability to support students and deliver programmes aligned with identified skills needs in order to secure allocations.

While demand for international education continues to grow, student mobility becomes increasingly intra-regional. Students from South Asia, West Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa increasingly opt for high-quality providers within their own regions or in nearby countries. Governments such as India, the United Arab Emirates, Malaysia, Saudi Arabia, and across Central Asia invest heavily in higher education infrastructure, attracting international branch campuses and promoting transnational education partnerships. These developments are supported by the expansion of credit recognition frameworks and multilateral agreements that allow flexible, modular pathways across institutions and borders.

This more distributed model of international education reduces the financial burden on families, shortens travel distances, and offers a hybrid experience - blending regional study with global credentials. For destination governments, it eases pressure on housing and services while ensuring that incoming students are concentrated in sectors of strategic value.

Ultimately, Regulated Regionalism advocates a balanced and managed approach to international mobility - one that retains academic quality and relevance while responding to national capacities and regional opportunity structures.

Hybrid Multiversity

Hybrid Multiversity envisions a future in which international education is delivered through coordinated, multi-site models that blend online, local, and global learning experiences. In this scenario, many students complete a substantial portion of their degree, often up to half, within their home country or region, either online or through a local partner institution. Shorter, structured periods of study abroad remain a central feature of the experience, focused on activities that benefit most from in-person engagement, such as internships and experiential learning, laboratory work, clinical training, language immersion, and professional networking.

Universities across regions develop common credit-transfer systems, harmonised curricula, and shared quality assurance standards to ensure seamless academic progression. Faculties collaborate across borders to align learning outcomes, assessment schedules, and moderation processes, enabling students to move between delivery sites with minimal disruption. The physical campus is repositioned as a specialised learning environment, prioritising facilities and experiences that cannot be easily replicated online, such as wet labs, design studios, and workplace-integrated learning.

Career development is embedded from the beginning. Micro-credentials earned during the home phase are formally integrated into academic transcripts, providing employers with early visibility of student competencies. Many programmes incorporate remote internships during the early years of study and require in-person placements during the global phase, supporting transitions to graduate employment. Policymakers facilitate this model by simplifying mobility pathways, streamlining visa processes, and recognising hybrid and online components for the purposes of post-study work.

Hybrid Multiversity advocates a more flexible, cost-effective, and coordinated form of international education - anchored in quality and global relevance while responding to evolving student needs, institutional capacity, and labour market expectations.

Talent Race Rebound

Talent Race Rebound outlines a scenario in which international education re-emerges as a central mechanism for attracting global talent in response to structural workforce shortages and demographic pressures. By 2030, major destination countries - including the United States, UK, Canada, and Australia - have implemented proactive policy shifts to address skills gaps in fields such as artificial intelligence, cyber and quantum technology, advanced manufacturing, biotech and healthcare and energy and agricultural innovation. Intake caps and administrative constraints that characterised the mid-2020s have been replaced by more efficient, student-centred systems. Visa approvals are processed within weeks, and extended post-study work rights, particularly in high-demand STEM disciplines, are now explicitly linked to structured, points-based migration pathways.

In this context, universities operate in deeper alignment with government and industry. Publicly funded national scholarships target priority fields, while private-sector partners co-invest in graduate internships and offer guaranteed employment outcomes. Research ecosystems are reinvigorated by multi-year public grants, upgrades to research infrastructure, and recruitment of globally recognised faculty, enhancing institutional attractiveness and capability.

Infrastructure constraints, particularly around housing, are addressed through coordinated investment strategies, including public-private partnerships in regional cities. This supports both increased enrolment and a more balanced geographic distribution of students.

For international learners, the proposition is compelling: a full-degree, on-campus experience that offers access to world-class academic environments, robust professional networks, and a credible path to long-term employment and residency. Families increasingly view the investment as a gateway to opportunity, and application volumes from larger emerging markets - such as India, Nigeria, Indonesia, and Brazil - rise sharply. International education, once primarily seen through the lens of cultural diplomacy, is now a key strategic lever in the global competition for human capital.

.jpg)