International education remains a defining force in the UK’s social and economic landscape - shaping talent pipelines, innovation, and global influence. The QS Global Student Flows: UK report applies a focused national lens to this global system, analysing how shifting demographics, policy reform, and competitive pressures will redefine international recruitment through 2030. Using evidence-based modelling across three scenarios - Regulated Regionalism, Hybrid Multiversity, and Talent Race Rebound - the report explores the future of student mobility, market diversification, and skills alignment, equipping UK higher education leaders with the foresight to navigate change and sustain growth.

Get a snapshot of the insights below. Download the PDF for the full report.

Executive summary

UK set to lead ‘big four’ in international student growth

UK international student enrolments are projected to grow 3.5% annually to 2030, faster than others in the ‘big four’, but slower than Europe’s 5% and below the post-pandemic surge. Growth will be shaped by tighter visa rules, shifting demands from students in key source markets, and rising competition from new regional hubs. Post-study work rights remain a key draw, but potential policy changes could erode the UK’s competitive edge. Africa and Southeast Asia are expected to drive growth, while the EU and Middle East contribute modestly.

India and China will remain the UK’s largest markets. Indian enrolments are set to rebound but at a slower pace, while Chinese numbers stagnate amid domestic economic pressures and improving institutions in China and the wider Asia Pacific region. African nations’ youthful populations and expanding middle classes will boost demand, but regional hubs are starting to compete for market share.

Intensifying global competition for international students

Reputation is playing a bigger role in student decision-making, with over 70% of UK-bound students (other than those from South Asia and Africa, where the number was over 60%) citing it as important. However, UK institutions face challenges as new hubs of high-quality education are emerging across the globe, particularly in the Middle East, China, India and Southeast Asia. At the same time, growing numbers of competitors are offering high-quality, lower-cost education which is also a factor in eroding the UK’s long-established standing.

Labour market demands offer an opportunity for UK universities

UK universities have a pivotal role in addressing the country’s growing skills shortages, with demand for nearly a million additional workers in digital, social care, construction, and engineering by 2030, according to Skills England. Aligning curricula with employer needs and embedding employability into education will be critical to closing these gaps, boosting productivity, and driving economic growth. International students, supported by pathways like the Graduate Route visa, are a vital part of this strategy, helping fill immediate labour shortages while sustaining long-term prosperity. To remain competitive, universities must strengthen industry links, co-develop future-focused programmes, and position employability at the core of their value proposition to both students and employers.

Three scenarios to enable strategic planning

To help UK institutions plan for the future, we have defined three evidence-based scenarios and applied a UK lens to assess what the future of higher education may look like in 2030.

- In the Regulated Regionalism scenario, the UK adopts stricter, centrally managed policies that prioritise reducing net migration over student growth, with bans on dependants, tighter visa compliance, and higher costs reducing demand. This selective approach makes enrolment more rigid, pushing students toward alternative destinations – including emerging education hubs across Asia - while UK universities face rising regulatory and reputational pressures.

- In Hybrid Multiversity, students complete much of their degree offshore, online or at partner institutions, before coming to the UK for shorter, hands-on study and industry-linked experiences. This flexible, lower-cost model sustains UK university revenue without adding to net migration but would require significant reforms to UK visa and education frameworks, and meaningful investments in new partnership development.

- Talent Race Rebound is a scenario where international education is repositioned as a tool for addressing UK skills shortages, with flexible visa pathways and targeted migration routes for priority fields like healthcare, tech, and engineering. This outcomes-based approach makes the UK more attractive to high-value students by linking study with clearer postgraduation career and residency opportunities.

Strategic challenges

The UK higher education ecosystem is uniquely positioned to drive innovation and economic growth, as well as continue supplying talent that industry requires. However, there are some key challenges that need to be addressed.

- An enduring skills gap between graduate skills and industry need: While graduates from UK universities are getting hired, they are not seen to be fully equipped with the necessary skills, indicating a misalignment between industry and UK higher education.

- Emerging hubs of international education outside the ‘big four’: The attractiveness of destinations in Asia for international higher education is growing. With growing international reputation for research, facilities and student life, emerging hubs of international education present new competitors in an already competitive marketplace.

- Forecast growth not enough to mitigate increasing costs: This report predicts that UK international student numbers are projected to grow 3.5% annually until 2030, but this will not be enough to fully support universities through a challenging financial period and increased costs. While sources of income for higher education in the UK continue to shift, new models of learning, funding through spinouts, funding grants and endowments will need to be fully utilised.

2030 outlook

Between now and 2030, the number of international students in the UK is expected to continue expanding at a moderate rate of 3.5% annually. Comparatively, other major Anglophone destinations are forecast to expand more slowly, but the UK is forecast to grow at a slower rate than the 5% anticipated for the broader European region. This moderation reflects tighter visa policies, particularly restrictions on dependants, alongside the global redistribution of students as new destinations gain appeal.

The forecast is slower than the immediate post-pandemic period where enrolments surged at a double-digit rate of 11% between 2019 and 2022, driven by pent-up demand and generous post-study work rights. The outlook for international student flows to the UK over the next decade is shaped by a combination of demographic trends, economic conditions in source countries, and policy shifts at home. After several years of volatility following Brexit and the pandemic, demand is expected to recover modestly, but the trajectory will be uneven across markets.

.jpg)

Several factors underpin the broader growth outlook. Post-study work rights remain a key differentiator, particularly for students from Asia and the Middle East. According to the QS International Student Survey, 60% of students from Asia are planning to remain temporarily or permanently after completing their studies. Exchange programmes, scholarships, and university partnerships will sustain medium-term pipelines, while economic expansion in source markets drives the middle-class demand that feeds long-term flows. At the same time, demographic contraction in key markets, cost pressures, and competition from emerging regional hubs temper overall growth, underpinning the outlook for UK enrolments expanding at a measured pace rather than in sharp bursts.

The upcoming period projects diverging trends in the UK’s two largest source markets; India and China. In India, following a temporary decline in 2024, enrolments are beginning to rebound. While growth is not expected to match the pace seen between 2019 and 2024 (43%), largely due to the earlier boost from the graduate route visa and the moderating effects of recent UK policy changes. Nonetheless, enrolments are projected to increase, supported by resilient demand from upper-income segments and the continued appeal of the graduate route as a pathway for long-term migration, which sustains selective inflows.

In China, economic strains are constraining household budgets, prompting prospective students to consider closer regional alternatives or domestic programmes. Undergraduate acceptances from China have also recently begun to drop reflecting broader shifts including increasing competition from domestic alternatives. Despite this, high-end segments remain willing to pay for Western degrees, and lower projected enrolments in the US and Canadian institutions could redirect some Chinese students to the UK. Overall, growth in Chinese enrolments is expected to be largely stagnant during this period.

.jpg)

In other parts of the world, Africa is emerging as a strong growth region, driven by rapidly expanding youth populations, rising middle-class incomes, and ongoing demand for affordable and high-quality international education, though affordability remains a key constraint in some countries. By contrast, Europe’s contribution to UK student inflows is more muted; flows are steady but modest, constrained by Brexit-related reforms and increased intra-EU mobility options. The Middle East is expected to be one of the slowest-growing regions for UK-bound students, as countries like the UAE and Kuwait increasingly restrict outward mobility while focusing on developing local universities to become regional hubs.

Although the outlook for the UK is stronger compared to its main competitors amongst English speaking study-destinations, this view is not without risks. The recent tightening of student visa policies, particularly the ban on dependants for all but a few postgraduate students, has introduced a significant element of risk. The UK’s policy landscape stands in contrast to traditional top destinations like Canada and Australia, which have long been favoured for their clear post-study work rights and immigration pathways. While Canada has introduced its own caps, and the US has its own visa issues, both of these factors could redirect some students to the UK. However, the UK’s own contractionary policies could diminish its competitive edge, particularly in the minds of students from markets like India, where a pathway to permanent residency has become a key consideration. This policy-driven uncertainty is compounded by the rise of new regional hubs. Destinations like Hong Kong (SAR) and Malaysia are actively targeting Indian students, while the UAE’s strategy to become a regional education hub and improve its domestic universities poses a direct competitive threat to the UK’s ability to attract students from across the MENA region.

The outlook is no longer a simple narrative of growth from all regions across the world. Instead, the UK’s future student flows will be a balancing act between attracting high-value students from stable and wealthy markets and mitigating the policy and economic risks in its most populous, and historically largest, source countries. The landscape will be marked by increased volatility, with a constant need to adapt to economic, demographic, and geopolitical shifts. The UK will likely see a more diverse student mix, with a growing number of students from dynamic economies in Southeast Asia and the Middle East, while flows from traditional mainstays like India and China, and from the post-Brexit EU, become more selective and policy-sensitive.

.jpg)

Our methodology

Global Student Flows initiative

The Global Student Flows (GSF) initiative comprises three core components: QS’ Open Source Framework for Global Student Flows, a proprietary Flow Mapping and Analytics Technology, and a Scenario-Based Forecasting Methodology designed to simulate over 4,000 discrete source-to-destination flows. Together, these instruments offer a comprehensive, 360-degree view of the global outlook for international student mobility.

QS International Student Survey

The QS International Student Survey offers an unparalleled view into pre-enrolled international students. The 2025 iteration draws on responses from over 70,000 students in 191 locations. The questions in the Survey are designed to enable higher education institutions to make sound decisions on recruitment and communication strategies. Now combined with Global Student Flows data, we offer a well-rounded view of where students are choosing to study, and how they make that decision.

Access more information about the methodology in the full report.

The three scenarios for 2030

Regulated Regionalism

Under Regulated Regionalism, the UK is likely to adopt a more restrictive and centrally-managed approach to international education. This scenario sees the government implementing policies aimed at reducing net migration rather than increasing student numbers.

As enrolment becomes more selective, application processes become more rigid, with a focus on reducing net migration. The ban on most international students bringing family members (dependants) to the UK, with the exception of those on postgraduate research courses and government-funded scholarships, continues to have a profound effect on applicants from key source markets such as India, Nigeria, and Pakistan, where bringing family was a major factor in choosing a study destination. According to the QS International Student Survey, students from Pakistan were twice as likely as the global average to bring a spouse or partner with them while studying abroad, with candidates from Nigeria more than three times as likely.

Under the current and proposed policies, universities must also meet more stringent visa compliance rules or face penalties, such as a minimum of 95% enrolment and 90% completion rates for their international students. Institutions could also lose their ability to sponsor student visas if more than 5% of their student visa applications are rejected. This has led some institutions to reduce or suspend recruitment from certain countries deemed “higher risk”.

Further regulatory complexity and rising costs could lead some students to consider alternatives. While the UK’s post-study work offer, the Graduate Route, has been subject to review and potential changes, uncertainty remains. This, coupled with higher visa fees and the dependant ban, has contributed to a decline in international student demand, particularly for postgraduate taught courses. These restrictive policies, while designed to reduce net migration, have created an opportunity for other countries, including those in the Asia-Pacific region, to attract students who might have otherwise chosen the UK. This includes students from major source markets like India and China who might be increasingly likely to choose education destinations which are closer to home.

This scenario reflects a future where student mobility is not unrestricted, but intentionally guided. The UK remains a major destination, but enrolment is increasingly selective, transparent, and aligned with broader national capacity and regional development goals.

Hybrid Multiversity

The Hybrid Multiversity model shifts the international student journey by moving the initial phases of a degree offshore. Students begin their studies either online or at partner institutions in their home countries. This allows them to complete the initial stages of their learning before travelling to the UK for a shorter, more concentrated period of on-campus learning. The in-person component is focused on practical experiences such as internships or hands-on training, which are difficult to replicate remotely.

This model relies on credit transfer systems to ensure a smooth transition for students moving between different delivery sites. Courses would be standardised to meet UK academic standards, allowing for a seamless integration of offshore and onshore learning. By recognising micro-credentials and modular study, universities enable students to progressively build their qualifications. The final stages of the programme in the UK often culminates in industry-linked experiences or capstone projects, which are crucial for preparing students for the workforce and are a key reason for the on-campus presence. This structure reduces the time and cost associated with a traditional three-year degree, making UK education more accessible and appealing to a broader international audience.

The UK’s immigration policies, which have become more restrictive, would also play a role. UK government forecasts indicate that the proposals in its April 2025 immigration White Paper aimed at tightening visa rules, could cut 12,000 applicants from the Graduate Route and 19,000 from the Student Route. The hybrid model could offer a way for universities to maintain revenue streams and international presence without contributing to net migration numbers, aligning with the government’s dual goals.

However, the UK would need to navigate this landscape carefully. The government’s current visa rules on remote learning are strict, typically allowing a maximum of 20% “remote delivery” for a course. Any wider adoption of a hybrid model would require careful alignment with Home Office regulations to ensure compliance and avoid jeopardising a university’s ability to sponsor student visas.

Courses would also adapt by offering preparatory learning through blended delivery. Students could begin learning remotely and travel to the UK to transition to immersive learning when academic study starts. Institutions would reserve their physical campuses for activities that require hands-on learning, such as lab work and employer engagement. Campuses would increasingly specialise, and digital infrastructure would be strengthened to support offshore learners.

This model presents a more affordable, flexible alternative to full on-campus degrees, offering a way for universities to maintain revenue streams and international presence without contributing to net migration numbers. The UK can leverage its strong global brand and the reputation of its leading universities by focusing on the quality of the on-campus experience. The country’s unique cultural heritage and vibrant city life remain powerful draws for students seeking an immersive international experience, even if a portion of their degree is completed remotely. The model would require major reforms to the UK’s visa and education frameworks.

Talent Race Rebound

Talent Race Rebound outlines a scenario in which international education becomes a strategic tool for addressing skills shortages and demographic challenges. Following a period of tightening visa controls, particularly a ban on dependants for most international students and proposed changes to the Graduate Route visa, the UK government, in this scenario, repositions international education as a targeted pathway to attract and retain younger, highly-skilled talent in priority sectors.

Under this model, the UK adjusts its policy settings to reflect a more selective, outcomes-based approach. While overall international student numbers are being managed, exemptions and targeted pathways remain for priority groups such as research students and those in high-demand fi elds like healthcare, engineering, and technology. In these areas, visa pathways and sponsorship rules are applied more flexibly, aligning education and immigration policy with the country’s national workforce needs.

In this scenario, the UK would also redesign its post-study work rights. Proposals to shorten the two-year Graduate Route visa could be re-evaluated, and the Skilled Worker visa could be made more accessible for UK graduates. This would involve a points-based system where international graduates with UK qualifications and relevant work experience earn additional points. Salary thresholds for jobs in critical shortage areas like IT and advanced manufacturing would also become more flexible. This incentivises students to pursue careers in sectors with the most pressing labour needs.

For international students, this model presents a strong value proposition, offering recognised qualifications, clearer migration pathways, and growing job opportunities in key industries. For the UK, this scenario would be particularly appealing to students from India, China, and Nigeria, who are the largest sources of international students for the UK.

Ultimately, this scenario is a shift from open-ended migration toward a more selective, outcomes-based model. International education is positioned not just as a valuable export industry, but as a crucial pipeline for skilled migration. Students who meet specific criteria in terms of age, language, and qualifications are recognised as future contributors to the UK’s workforce and economy.

International student trends

Using insights into what students want to future-proof your strategy

The growing influence of reputation on student choices

The reputation of an institution is of increasing importance to students looking to study in the UK. In all regions except South Asia and Africa, over 70% of students say reputation is important when choosing a university.

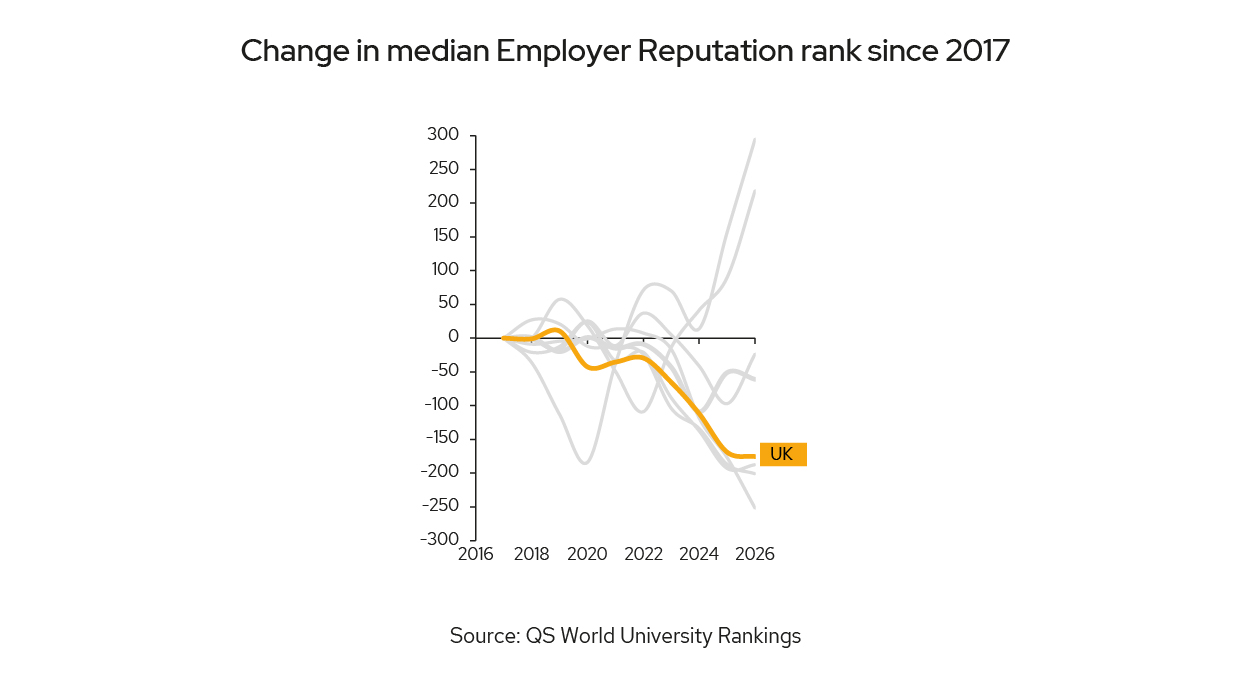

Similar to major markets across Europe, this rising importance is arriving at a bad time for UK institutions. The median Employer Reputation rank of UK institutions is down by over 150 positions since 2017. Academic Reputation performance is also down, but only slightly. In both charts, we see some countries that have rapidly improved their reputation – these countries may threaten the hegemony of the ‘big four’ as they provide high-quality education at a lower cost than the Anglophone destinations.

Combined, these factors present an unfortunate situation for UK institutions.

Employability on students’ minds

The issue of UK institutions’ Employer Reputation rank declining is further exacerbated by students’ increasing focus on post-study employment outcomes when making study decisions. 50% of students looking to study in the UK said information about work placements and links to industry was useful – the second highest answer. Students from South Asia, East Asia and Africa are the most likely to say that this information is useful.

.jpg)

Regardless of source region, over 50% of UK-bound students said that they chose a course because it allows them to learn new skills for their career.

An institution’s Employer Reputation can be significantly influenced by the outcomes of its graduates. In the UK, institutions’ Employment Outcomes are marginally worse than their Employer Reputation. This disparity suggests that while UK graduates are getting hired, their employers are not entirely satisfied with graduates’ skillsets. To create parity, UK institutions need to make graduate skills development a core component of existing and upcoming curricula creation. Ensuring that graduates have the appropriate mix of skills to meet the existing and future demands of local employers should be central to this strategy. In doing so, institutions can transform their capacity to become drivers of economic growth and enhance their reputation among employers.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)