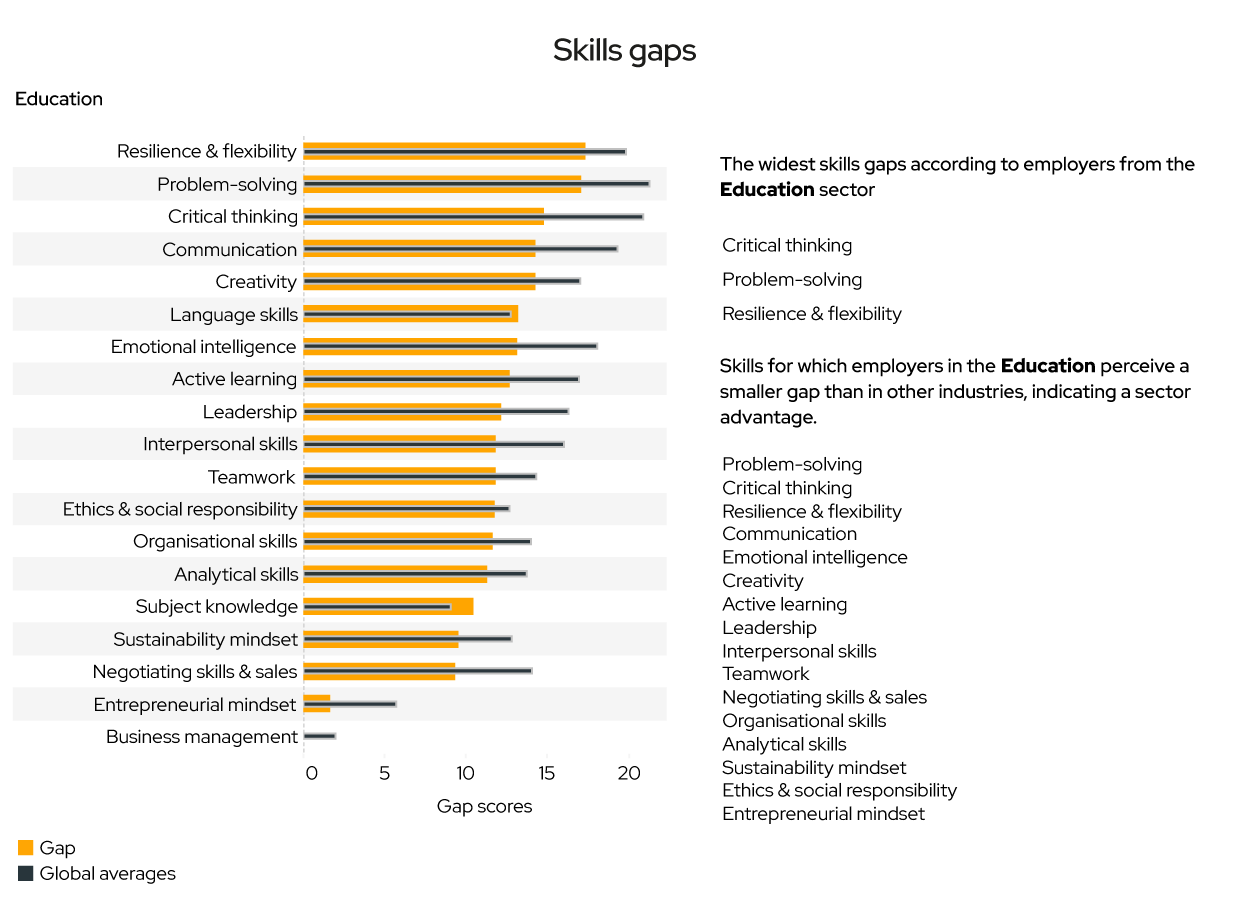

Across thousands of employers surveyed globally, the same gaps come up again and again:

- Graduates struggle most with critical thinking and judgement, not subject knowledge.

- Problem-solving and communication are among the widest gaps across industries.

- Employers increasingly value adaptability and interpersonal skills as AI reshapes work.

The skills employers describe as missing are rarely technical or sector-specific. They’re the transferrable capabilities that determine whether graduates can use what they’ve learned in real workplaces - especially when problems are ambiguous, time-pressured, and increasingly shaped by AI.

The five skills universities need to build now

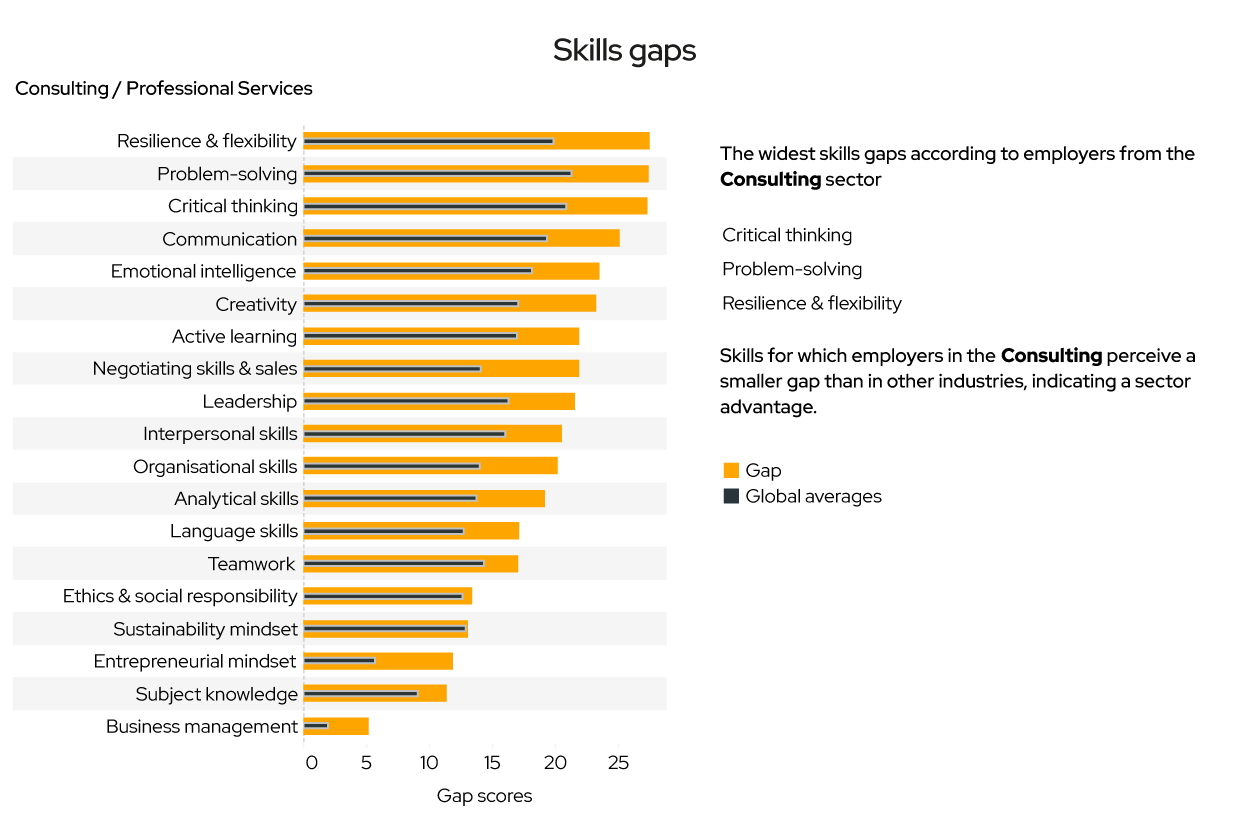

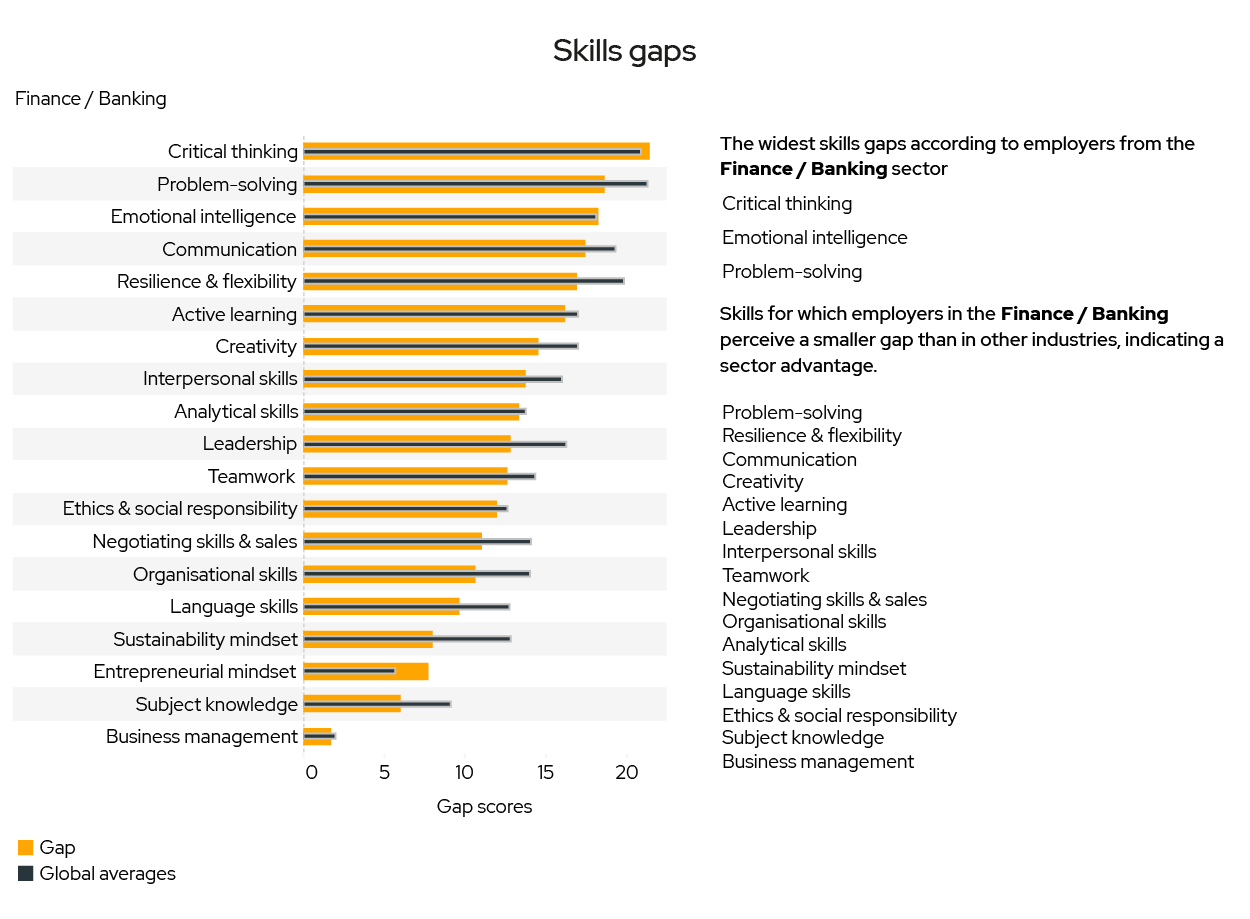

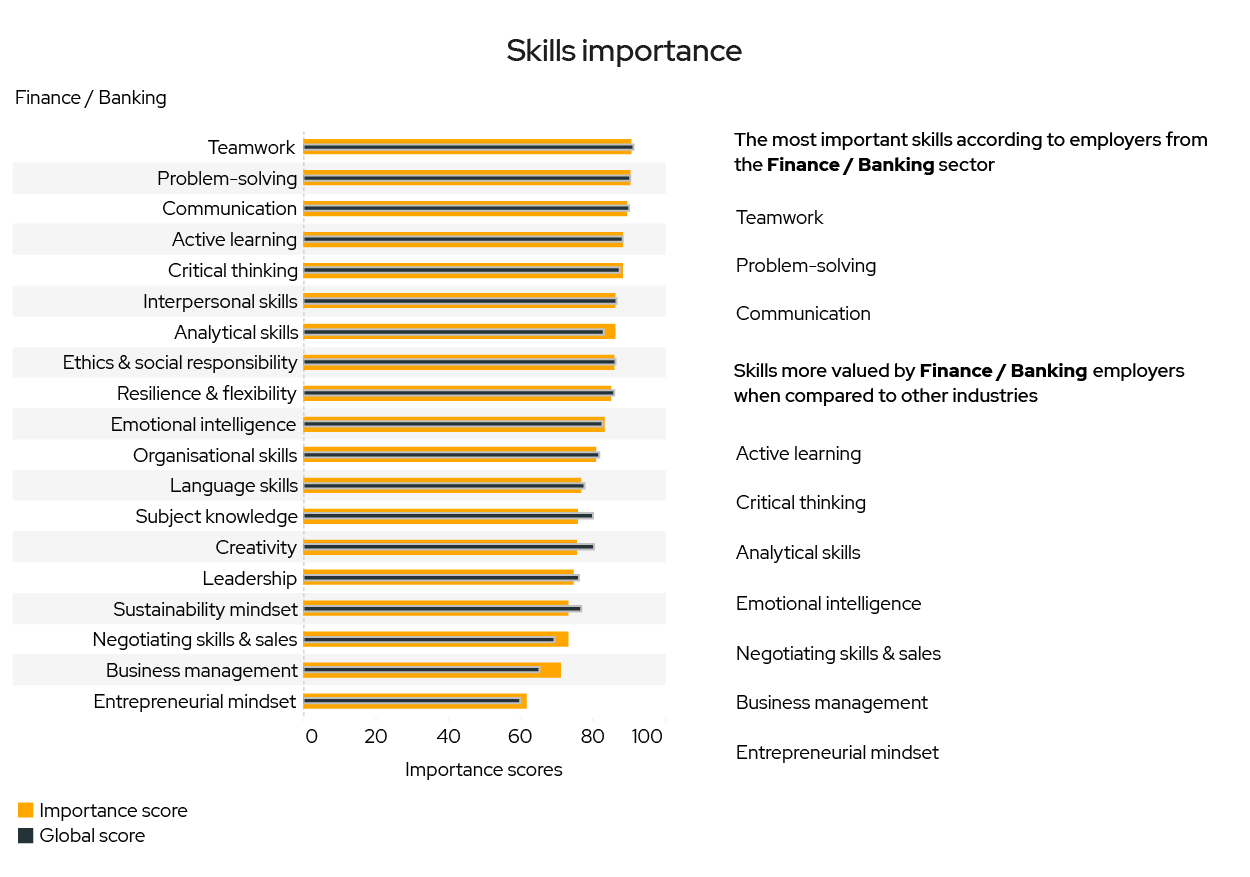

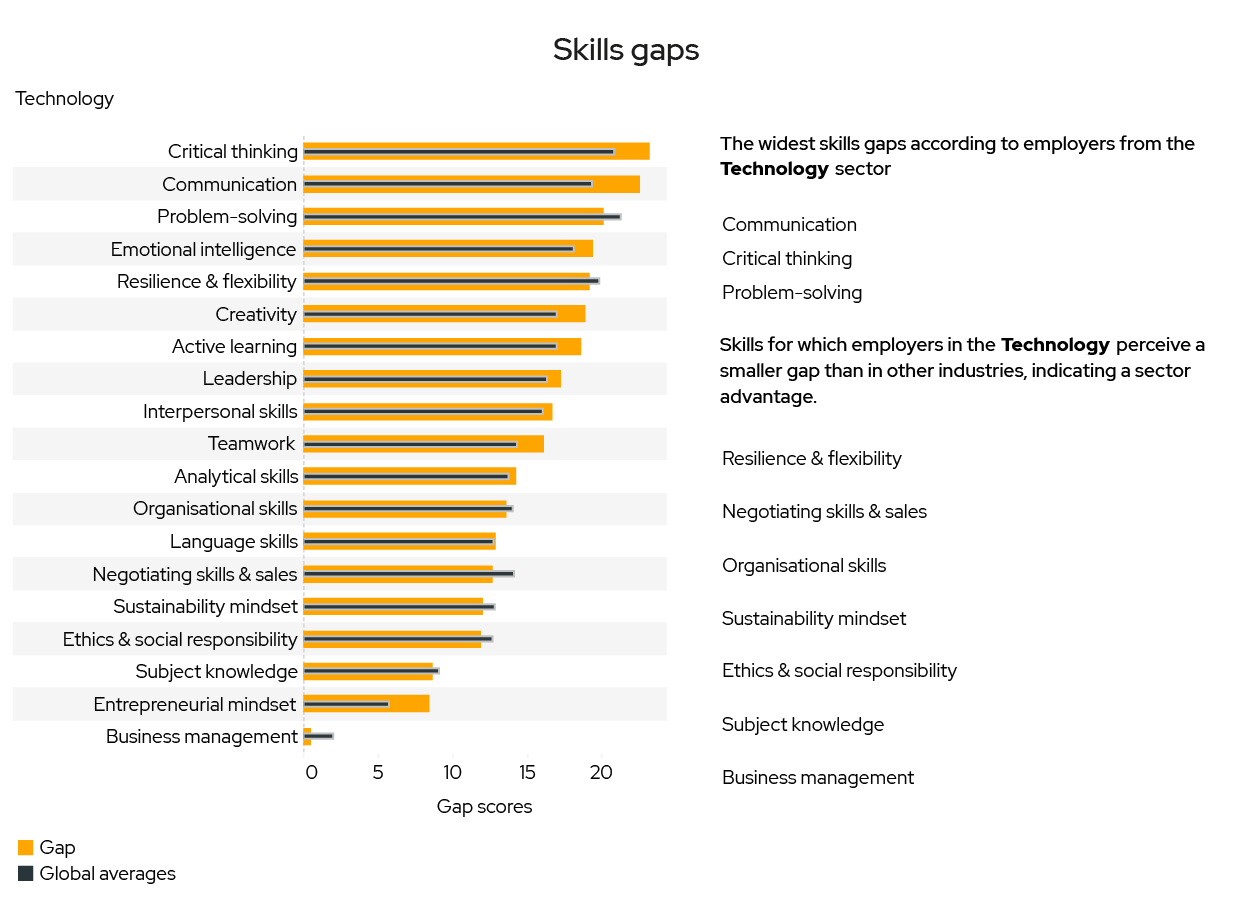

When employer-reported skills gaps are compared across industries, a clear pattern emerges. The same capabilities consistently rise to the top. Far from being industry-specific, these are fundamental skills that determine how effectively graduates apply their learning.

- Critical thinking and judgement

- Problem solving

- Communication

- Resilience, flexibility and adaptability

- Emotional intelligence and interpersonal skills

Critical thinking and judgement sit at the centre of what employers say is missing. Across sectors including consulting, education, and healthcare, employers report that many graduates struggle to challenge assumptions, evaluate evidence, and make sound decisions in complex situations. As AI makes it easier to generate plausible – but perhaps incorrect or vague - answers instantly, this gap becomes more consequential.

Closely linked is problem-solving, one of the most consistently reported skills gaps in the QS data. Employers are not saying graduates lack theoretical understanding; they are saying graduates struggle to apply that knowledge to messy, time-pressured problems with competing constraints. This gap appears across almost every industry, and in some - such as finance - problem-solving ranks among both the most important skills and the widest gaps.

Communication is another recurring concern. In the technology sector - one of the fastest-growing areas of the job market, with the Future of Jobs Report 2025 identifying roles such as AI specialists, big data professionals, and software developers among the world’s fastest-growing jobs - employers still report communication as one of the widest skills gaps in the QS data. Many graduates can communicate academically but struggle to write and speak with workplace clarity: concise, persuasive, and tailored to different audiences.

Employers also highlight gaps in resilience, flexibility, and adaptability, particularly in fast-moving sectors such as consulting, finance, government, education, manufacturing, and media. Modern work is defined by change, ambiguity, and continuous feedback, yet many employers feel graduates are underprepared for these conditions. In the education sector itself, resilience and flexibility appear among the widest reported gaps.

Finally, the data points to shortfalls in emotional intelligence and interpersonal skills, especially in people-facing sectors such as HR, hospitality, healthcare, and the non-profit sector. But these emotional intelligence and interpersonal gaps aren’t confined to people-facing roles: they also appear across finance, government, defence, and energy. Employers report weaknesses in collaboration, empathy, conflict management, and relationship-building. As work becomes more team-based and AI takes on more transactional tasks, the human side of work has not diminished, but has become the differentiator.

What employers are actually saying

QS’s Global Employer Survey - the data we’re using in this article - captures what employers say they need most from graduate talent, including where they see the biggest skills gaps. Drawing on responses from thousands of employers worldwide, it offers a global view of how institutions and programmes are perceived in the hiring market and informs the Employer Reputation indicator used across QS Rankings.

When we look at skills gaps across industries, a consistent pattern emerges: the capabilities employers most often say are missing align closely with the five skills highlighted above. Employers are not primarily pointing to a lack of knowledge. Instead, they emphasise the ability to apply knowledge in real workplaces - thinking critically, solving problems, communicating clearly, staying resilient in the face of complexity, and working effectively with others.

This distinction matters. Subject knowledge and business management tend to sit lower on the gaps list, suggesting employers expect these to develop on the job. What they are less confident can be “picked up later” are the transferable capabilities that cut across roles and sectors. Taken together, the message is clear: universities are not being asked to teach more content, but to design learning in ways that build these five capabilities through practice, feedback, and assessment.

Why these skills don’t develop by accident

These capabilities are not easily acquired through content-heavy curricula or assessment models that reward recall and compliance. Critical thinking, communication, and adaptability develop through practice: grappling with uncertainty, receiving feedback, working across disciplines, and reflecting on failure. When learning environments underprioritise application, these skills remain underdeveloped, even among academically strong students.

As generative AI tools become embedded in both education and work, the ability to evaluate, interpret, and apply information is becoming more important than producing information itself. This has direct implications for how universities assess learning. Tasks that privilege judgement and real-world application are far more closely aligned with the skills employers say are missing.

What this means for universities

The message from employers is clear. The future value of a degree will be defined less by the volume of knowledge it certifies and more by the capabilities it helps graduates build. In 2026, universities that succeed will be those that treat skills development not as an add-on, but as a core design principle of learning itself - ensuring graduates are not only qualified, but equipped to thrive in an AI-enabled, fast-changing world.

.jpeg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)